The following is a lightly edited transcription from The Punch Out with Eugene Puryear, a daily news podcast that comes out Monday through Friday, 5pm ET. Subscribe here.

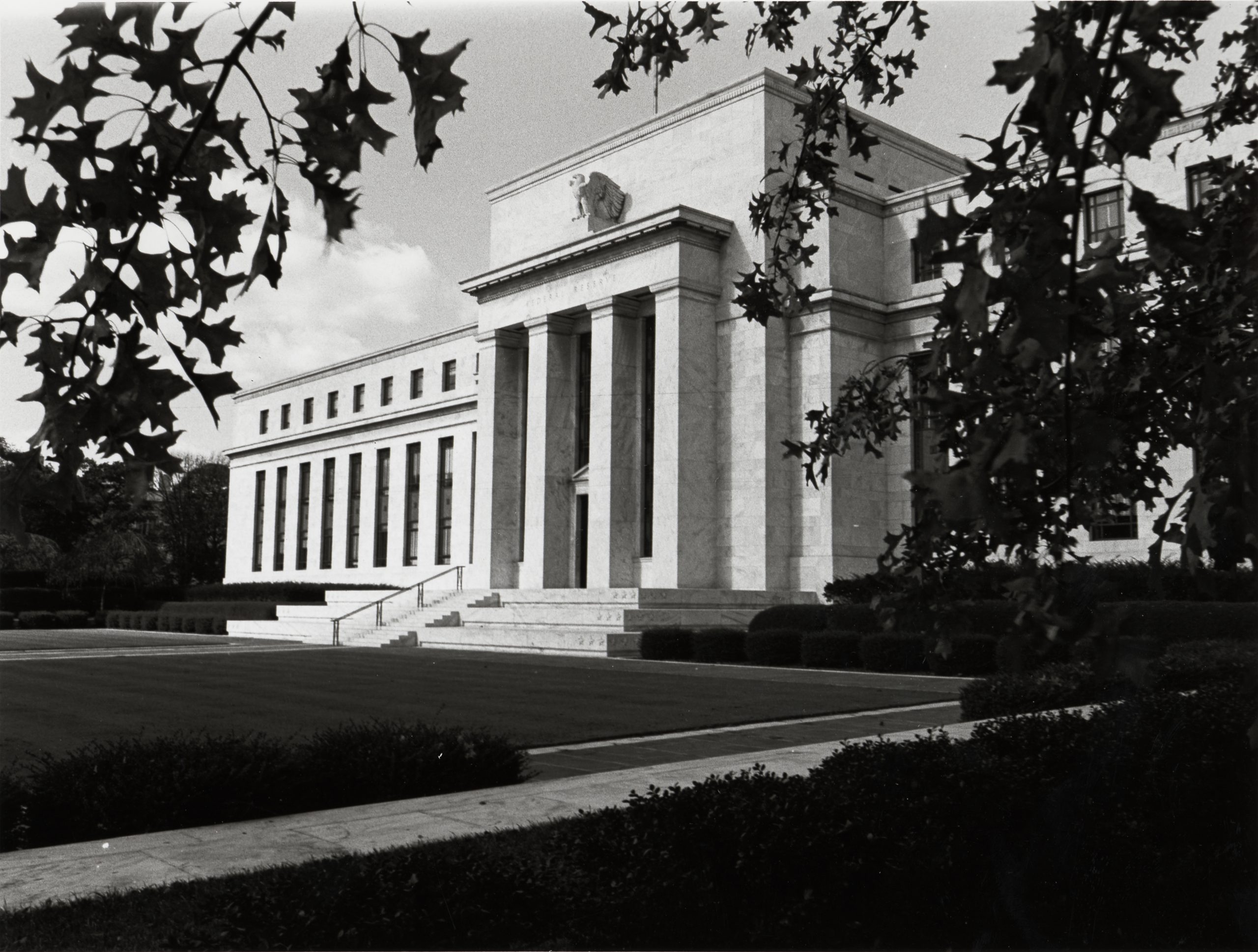

The Federal Reserve: we’ve all heard about it, most of us know it has a lot of power, but beyond that what do most people really know?

It’s an important question for all of us because the Federal Reserve is likely to again increase interest rates to a level that could cause a recession. In their adjustment of interest rates, they will determine whether millions of people work and whether their wages and hours will be cut. With that kind of power, every working-class power should know what this institution really is, how it came about, what it does and who it serves.

The easiest way to understand the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) is that it’s the institutional representation of the slogan “too big to fail.” It is essentially a partnership between the government and Wall Street, based on the recognition that capitalism intrinsically causes crises and boom-bust cycles. And, rather than resolve this root problem, the Fed is supposed to be there (in theory) to help try to maximize and prolong the boom and minimize the bust.

This sounds good in theory, but as always the question is in whose interest does this agency intervene? In practice the Fed is subject to the demands of the biggest banks and corporate America, despite a figleaf of public participation. The Fed is how Wall Street runs its casino-style capitalist roller coaster we’ve all gotten used to, with only a minimum of oversight, while using our hypothetical tax dollars to back it all up.

Let’s start with what the Fed does. The Federal Reserve technically has three objectives, as prescribed by Congress: maximizing employment, stabilizing prices and moderating long-term interest rates. Over the years all sorts of things have been added to its mission, including a range of bank regulations, maintaining the “stability” of the economy and providing certain financial services for banks.

The basic core of the Fed’s function is to manage monetary policy — that is, the money supply — and act as the “lender of last resort” to financial institutions. On a day-to-day basis most of what the Fed does is manipulate these “monetary policy tools.” What they are doing is essentially regulating the flow of credit in the economy. At certain points they make credit easier to get, so as to stimulate lending and therefore economic growth, and at other times they make credit harder to get, to cool down the economy.

There is an old saying at the Fed that their job is to take the punch bowl away just before the party gets started. That’s because the Fed operates on the basis that the economy is bound to not only go up and down — that the very success of capitalist production sows the seeds of its own demise; the bitter fruit of an economic boom is that it guarantees a crisis. So the Fed hopes to head off a larger crisis by making it happen a bit before it naturally would, hopefully making the decline more manageable, even if it’s still painful—for the working class in particular. Then the Fed hits the gas a bit to help the economy get going again after the house of cards has totally collapsed.

The main tool the Fed uses to make these moves are its “open market operations,” governed by its Open Markets Committee, which is the main day-to-day body managing the economy. If the Fed wants to make it easier to get credit, they put money into the system; if they want to make it harder, they take money out. The way they do that is through the sale and purchase of U.S. Treasury bills (“T-bills”), which are a type of short-term bond. When the Fed wants to put money into the system and make it easier to get credit, they sell Treasury bills via auction.

A number of large financial institutions are “primary dealers” of the Fed, which means they handle their transactions. As a stipulation for this lucrative business, they must buy the Treasury bills offered at auction. Then they have to unload them — the same way they would trade other securities (which are stocks, bonds, mortgages, and other tradable assets). The bottom line is that it increases the amount of money banks have to lend.

The reverse is also true. If the Fed wants to take money out of the system, then they buy T-bills on the open market. On a daily basis the Fed conducts a bunch of purchase and sale agreements in order to change the amount of money in the system. That shapes the overall interest rate, or the rate that a company or individual will have to pay to borrow from banks, also called the “prime rate,” in the economy. But how?

Two interest rates in particular affect the prime rate. This first is known as the “federal funds rate.” For a bank to be a member of the Fed, they have to keep a certain amount of money in the Federal Reserve. The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks that are a part of the Fed loan money to one another from the reserves they keep. That is the center of gravity around which banks determine how much they are going to lend to you — the prime rate — based on how they’d measure risk when lending to each other. The federal funds rate is actually a range which the Fed sets. They use their “open market” operations—essentially the purchase and sale of T-bills—to manipulate the market to reach the target rate.

The second interest rate that affects the prime rate is the Federal Reserve’s “discount rate.” This is the interest rate that banks have to pay when they borrow from the Fed directly, and this kind of borrowing is called using the “discount window.” The Fed intentionally sets this rate higher than the federal funds rate to make it more appealing to go to financial institutions in the private sector before coming to the Fed for money. It is considered very bad form to go to the discount window unless absolutely necessary, and the discount rate is essentially a “penalty rate.” Since the “prime rate” is for borrowers in good standing, banks will likely set prime rates below the “penalty rate.”

So by manipulating the federal funds rate and setting the discount rate, the Fed creates the foundation for the prime rate and the overall interest rate of the economy. If you’re not issuing or taking out loans, perhaps you think this does not matter to you, but it does. This is very important to the overall situation in the economy. If the rates are too high, which makes credit too tight, then the economy can’t grow, and capitalists are tighter with their money with respect to new investments and wages. If the rates are too low, which makes credit looser, the economy and speculation will grow out of control.

The Fed is thus using its own subjective evaluation of the economic situation to decide whether to grow or contract the economy. This a tremendous amount of power since it indirectly determines who works, who doesn’t and for how much.

The Fed also acts as a “lender of last resort”—going back to the “too big to fail” concept. At the end of the day, the Fed will ride to the rescue of the financial markets, which it can do in various ways. The main way it does this is by setting up various “facilities.” This sets up a method for lending money, indirectly and directly, in order to prevent a certain sector from collapsing due to risky bets going bad for whatever reason. Among the more well-known of these are the Primary Dealer Credit Facility and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility.

These “facilities” can work in many different ways, but the basic setup is this: If there is a problem in a particular subset of the financial markets, the Federal Reserve will loan money to that part of the market based on whatever terms it considers appropriate. In essence, the Fed is buying whatever the market won’t buy in order to make sure commercial activity can continue.

Since these transactions are what grease the wheels of the whole economy, the Fed is looking for where bad bets might bring down the whole economy or a big chunk of it, and they inject a bunch of credit to try to prevent that from happening.

This means that the Fed decides who is too big to fail and when, what losses the system can absorb and which ones it can’t. This too is tremendous power. It can collapse giant banks and the associated corporations they’ve lent to, or save them. They can and do pick “winners and losers” based on their own evaluation of who needs to be saved and how.

The Fed also holds tremendous power in its regulatory apparatus. It determines how much capital the member banks of the Federal Reserve have to keep in reserve, which then structures the financial decisions and risks that the big banks take.

As you can see, the Fed really is embedded at the heart of the economy. While it presents its decisions as all due to cold hard facts, the truth is that it’s also based on their own conjecture, and based on their own biases and premises. For instance, they insist now that they have to keep raising interest rates to address inflation, but as we have noted a number of times on this show, raising taxes on the wealthy would be far more effective. The Fed is moving ahead with actions that are likely to induce a recession because they view their way as a necessary and natural consequence, which is easy for them to say. It speaks to the frame of mind and class interests of the people who make up the Federal Reserve.

The domination of the Fed by the big banks has its own important history. The Federal Reserve wasn’t formed until 1913. Before that, starting around the 1880s, things ran somewhat similarly but on an ad hoc private basis. The biggest banker was JP Morgan. On the basis of being the largest banker, his bank took on the task of determining the winners and losers himself.

Morgan would organize the big New York banks to use their reserves, or sometimes borrow against those reserves from the big European banks, to lend out credit to smaller banks around the country to meet increases in demand for lending during an economic upswing. But as the banking system overall would take riskier and riskier bets to make as much money as possible, eventually the big New York banks led by Morgan would refuse to reimburse their losses. The overextended banks would fail, and as you can imagine the dominos would fall and the economy would crash. Now often this worked out well for Morgan and friends, because they could protect themselves, and then go pick up the pieces of the failing banks and add them to their giant financial empire.

However, for the working class and the small farmers, this system was very bad, since it meant recurring crashes without any sort of mechanism to regulate them. In the Populist movement of the late 1800s, ordinary working people started raising the issue that these policies could be regulated. They noted that if the banks were too big to fail (to use a modern phrase), then they needed to be managed by democratic forces to curb the excessive risk taking. And if decisions had to be made about capital allocation, picking winners and losers, then the decisions should not just be made by the biggest bankers, who of course never made themselves losers.

In 1907, there was a major economic panic, so bad that even Morgan couldn’t save things. The government had to step in with emergency loans and this changed the whole conversation. Morgan and his New York bankers couldn’t handle the crisis, because as corporations got bigger all across the country, so did the regional banks that managed their money. Not only did that make the task of management bigger, but these new players increasingly resented having an ad-hoc committee in New York making decisions that affected the entire banking system all on their own.

So organizations of bankers started plotting and planning. They came up with a basic scheme similar to what the Federal Reserve would end up looking like, which they then had introduced as legislation. The biggest question that became an issue was what role would the federal government play? Would the government just let private bankers run the whole thing?

To make a long story short, a compromise was struck. The regional banks within the Federal Reserve System would be owned by the commercial banks, meaning the commercial banks would be the shareholders of these institutions. The regional banks would also play a big role in managing things, but the U.S. president would appoint a number of people to manage the new central bank alongside them.

That, in essence, is the structure created by the Federal Reserve Act. The bottom line here is that the Federal Reserve came about as an effort of the financial industry to create a system backed by the “full faith and credit” of the government, but one that could still manage the banking system in a similar way: benefitting bankers as a whole and helping them maintain their core role as masters of the economy. With the legitimacy of government backing, they could continue to control the economy, get bailed out if they made poor decisions, and keep making money hand over fist.

Under the Federal Reserve Act, every nationally chartered bank must be a member of the Federal Reserve system; banks with only a state charter can join if they want, but it’s not required. Something like 38% of current banks are members of the Federal Reserve system. These banks belong to one of 12 regional banks, which pick their own board of directors and a president who has to be the CEO of a bank. The U.S. president appoints seven members to the top body of the Federal Reserve, the Board of Governors. Those seven appointees and a five of the 12 regional bank presidents (on a rotating basis) sit on the Federal Open Markets Committee, which leads the decisions on what the Fed is going to do.

The influence of banks and the ultra elite on the process works in a few ways. First, directly, in the fact that the regional Federal Reserve bank boards are dominated by banks and corporate heads. Three members of each nine-person regional board have tobe be bankers (called Class A). Class B and C members are supposed to represent the public but these so-called “public representatives” are almost all corporate CEOs with a handful of labor leaders or heads of major philanthropies thrown in.

Ostensibly this direct financial influence is supposed to be outweighed by the Governors appointed by the U.S. president who are confirmed by the Senate. However, when you look at who serves on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, you’ll note they come almost exclusively from high level corporate backgrounds, the high levels of elite academic institutions, or the highest levels of government service (which often means they also spent time in the corporate world and the highest most elite levels of academia).

The Senate provides no real check either. Of the 28 members of the Senate Finance Committee, 24 have the “Securities and Investment” industry among their top 5 donors. So it’s clear there is a sophisticated multi-layer elite filtering system at work at the Fed.

Wall Street is directly embedded throughout the process, and the so-called public representatives are primarily made up of people whose entire careers have been spent as a part of or in service to the interests of Corporate America, and they are chosen by politicians whose entire positioning is based on donors from the same class. The U.S. president also has very limited grounds to get rid of Fed Governors, and no power to get rid of the bank presidents. So, once appointed, Fed officials have a huge amount of autonomy.

In a moment where many U.S. institutions are rightfully being questioned for giving small minorities large amounts of power over the broad majority, the Federal Reserve has to be among them. Masquerading as a “public entity,” a club of the richest, most powerful people in the country, backed by tax money, use it to control the economy in the way that they deem fit—which is to facilitate the long-term continuation of the broader capitalist financial structure, booms, busts and all.